Shared cross border challenges at TechCamp

Air quality is a tremendous challenge faced by millions of Indians, Pakistanis, Nepalis, and others in the region. Like other threats our world is facing, air quality doesn´t respect national borders. With this in mind, attendees at TechCamp Kathmandu, held July 29-31, 2019 in Kathmandu, Nepal, developed a cross border plan to build a network of air quality monitoring sensors across South Asia to improve understanding of pollution’s transborder implications. The TechCamp’s main focus was air quality, which is a cross-border issue that affects countries across South Asia. One key to TechCamp Kathmandu’s success was bringing people from many different sectors together to work on this air quality challenge.

Indians Ronak Sutaria and Badri Chatterjee, Pakistani Abid Omar, and Sri Lankan Ashani Basnayake attended TechCamp Kathmandu and worked closely together to analyze the problem, and more importantly, develop practical solutions. Both Omar and Sutaria have extensive experience working in air quality advocacy. Sutaria began his startup, Respirer Living Sciences, as a data journalism nonprofit democratizing information about air quality, and his educational background is in sensor networks. Omar had already created a grassroots network of air quality monitors in cities across Pakistan, publishing off-the-charts recordings on Twitter.

During the TechCamp, Omar, Sutaria, Chatterjee, and Basnayake found that their goals of improving air quality monitoring resources were aligned, despite their countries of origin. “We were like, this is a challenge, and we’re actually the right people sitting together— Let’s figure out what needs to be done. The next step came very naturally,” Omar says.

Solution

Omar and Sutaria’s group recognized that the first step was ensuring that both countries had sufficient AQM data coverage. Because pollution blows throughout regions without stopping for political demarcations, data must be tracked on a regional level. After collecting this data, they could publish it and make regional-level improvements possible. “Because air pollution doesn’t see any borders,” says Sutaria, “You have to take a holistic approach and look at the whole region. The first step is to install the same kind of monitors on both sides of the border.”

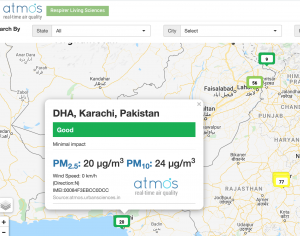

Government-recommended monitoring equipment costs about $15,000, which is prohibitively expensive when thousands of monitors are needed to have enough coverage. Sutaria’s Mumbai-based startup, Respirer Living Sciences, develops local sensor based air quality monitoring networks using devices called “Atmos.” Sutaria’s monitors, cost about $500 and are comparative in accuracy. “India has evolved a fair bit in terms of air quality policies and monitoring,” says Sutaria. It already has about 250 government-owned monitors imported from the United States. Pakistan has just a handful, meaning that there is a great imbalance of resources.

Omar had already been building a citizen-led network of home air monitors across Pakistan due to this difficulty of access and expense of regulatory-grade equipment, but he needed more accurate monitors. So, the two were were selected for a TechCamp grant to kickstart production of Atmos monitors to send to Pakistan. Despite a few hiccups— the monitors had to be shipped through Dubai because India and Pakistan do not maintain trade relations— Omar had already begun to establish a network of sensors collecting data by mid-March.

Pandemic

In March, a new enemy began to attack the world’s lungs. The COVID-19 pandemic spread like wildfire and countries went into lockdown in a matter of weeks. Although this new reality has changed how Omar and Sutaria work, it has not entirely been detrimental. Sutaria’s nonprofit, Respirer Living Sciences, was recruited to test N-95 face masks as a part of rapid response efforts. The technology used in Atmos machines is the same as what is used for face mask testing. It is important to be able to determine which face masks can effectively filter PM 2.5 particles from the air. “Counterfeit masks are coming in,” says Sutaria. They put all these labels on them, but you’re betting your life on the mask.” He also encourages individuals to test their own masks and has been posting resources online.

Omar has been busy, too. “I work in the essential services sector in my day job,” he says. “I was going out in the streets every day. It was pin-drop silence. Like a ghost city.” Omar, like many, saw that the skies were noticeably more blue than usual, a surprising occurrence that’s been covered on international media.

Because Omar had been continuing to take air quality measurements as planned, he was able to compare them to the previous year’s data. That’s where he noticed something surprising. “While there has been a reduction in pollution levels, it was still above safe limits. We’re still not at the standards that are considered normal in the U.S.”

Why is pollution still so high when the world was supposed to be shut down? “ Certain industries cannot shut down,” Omar says. “It is a vast problem without any one simple solution.”

Looking Forward

Despite the challenges, Omar and Sutaria are hopeful about the future of air quality advocacy in South Asia. Both emphasize the importance of citizen action and working with the government to make policy change. Transborder communication is extremely important in these conversations. “The sources are on both sides and pollution is blowing across the border,” says Sutaria. “If an intervention happens from our side, we might end up paying a smaller price in the health effects of the pollution.”

Their project is only the beginning of what may hopefully become an extensive network of affordable, citizen-led air quality monitoring stations across South Asia. Data collected will help communities work with policymakers to make practical changes to improve air quality across the region.

“Air quality and good governance are directly related,” notes Omar. “Having a good sky means you have a good government, because they’re able to continue economic balance while keeping pollution in check.” With the right steps, this change is absolutely possible, thanks to these hard-working advocates who understand the connection between collecting data and the activism that will make the skies blue again.